by Ebony Bennett

[Originally published in The Canberra Times, 01 June 2019]

I come not to bury polls, but to praise them. While everyone – including the polling companies it seems – was shocked by the election results, the media and the public are learning the same lessons that political parties have had to. And it’s a hard one: polling is just a tool.

But first, what did go wrong? The polling companies themselves are bewildered and baffled. David Briggs from Newspoll reflected that it had used exactly the same methodology in 2019 as it did in 2016, when its elections polls were “the most accurate there has ever been” once measured against the actual result.

A supporter watches the tally count at the Federal Labor Reception in Melbourne on election night. Picture: AAP

Enormous expectations for Labor were built on the back of nationwide two-party preferred polling results over two years that, in the end, proved to have little to say about what was happening in individual seats.

In actual fact, the 2019 election results were remarkably similar to the 2016 election. It’s just that expectations were wildly different, as Antony Green observed on the night.

There are many things that could be going wrong: sampling error, measuring One Nation’s lower house vote when they only stood in about 40 per cent of seats, incorrect preference allocation, a high undecided vote breaking differently than expected thanks to a late swing-the list goes on.

No one will be more invested in explaining what happened than pollsters. Polling companies have nothing to gain from presenting inaccurate polling. Their whole business depends on providing accurate results that truly reflect what the population is thinking. Any pollster with a reputation for inaccuracy or bias would find themselves quickly out of work.

Nobel Laureate in physics and Vice Chancellor of ANU Professor Brian Schmidt talked about knowing something was wrong with the polls because the mathematical odds of 16 polls returning the same small spread of results was “greater than 100,000 to 1”. But how were those of us who hated maths in school supposed to know?

In journalism school you are taught – or at least you were 20 years ago when I studied it – when reporting polling to always report the sample size, methodology, margin of error and ideally, confidence interval. But, during an election campaign, who wants to clearly explain the uncertainties of polling on the front page of the paper when your headlines scream the result as all but gospel?

We’ve fallen into the trap of using polling as a precision tool, when actually it’s a tool for accuracy. That doesn’t mean we should abandon polling altogether, we just have to use the right tool for the right job.

To understand the difference between precision and accuracy, think of a dart board. Precision is getting all the darts in the same place on the dart board every time, accuracy is being close to the bullseye.

The polls leading up to the election were precise (tightly clustered) but a little inaccurate (off the bullseye).

Polling is still the best and most accurate (not precise) method we have, short of direct democracy ballots, of tracking public opinion on issues like climate change, health care, national security and education, and there’s no evidence the polls are wrong on any of those in any meaningful way.

We don’t need precision to tell us if there are strong, or mixed, or no particular views about an issue across the population, we just need to hit close to the bullseye.

But just as we now use economic modelling to determine policy instead of as a tool to help us understand the impact of a policy we similarly abuse polling. To justify expanding its McArthur River zinc-lead mine in the Northern Territory, Glencore commissioned Aurecon to estimate the project would generate tax and royalty payments of over $1.5 billion. The modelling estimated its payroll tax payments out to the year 3017. Yes, that’s a thousand years away. That’s not only ridiculous, it’s virtually useless as a tool for helping determine policy.

Just as an economic model can’t tell you what to do, a poll can’t tell you exactly what is going to happen.

But the polls got it right that a majority of Australians supported marriage equality and there’s every reason to believe the polls when they show a majority of voters support renewable energy (especially solar), want lower power bills, prioritise a strong economy and jobs, and oppose drilling for oil in the Great Australian Bight.

We still have to be wary of bias. The US Department of Energy this week rebranded fossil fuels as “molecules of freedom”. Now, if you ask people if they support drilling for “molecules of freedom” in the Great Australian Bight, you’re bound to get a lot more support than if you ask about drilling for oil, which is opposed by 60 per cent of Australians and 68 per cent of South Australians.

And without polling, what else do we have to rely on to gauge community support or opposition to policy issues? Anecdotes? The gut feelings of Ministers like Matt Canavan?

Just as an economic model can’t tell you what to do, a poll can’t tell you exactly what is going to happen.

Opinion polling is still incredibly useful, but it cannot replace facts when crafting public policy any more than economic modelling can.

Matt Canavan this week told business leaders they were out of step with the Australian people on the issue of a carbon price. That’s not true, as an Australia Institute poll of a nationally representative sample of 1459 people, taken between October 26 and November 6, 2018, showed 63 per cent of people support a price on pollution to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. But it’s also largely irrelevant.

Climate change is a reality the Australian business sector, our corporate regulators and the public are concerned about and must deal with.

The science on global heating doesn’t care about economic modelling or the opinions of Matt Canavan, or anyone else. The temperature hit 29 degrees in the Arctic this week. The UN says one million species are at risk of extinction. And Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, which trap heat in the atmosphere, are still rising.

Ironically, it’s a fictional TV series, albeit based on reality, that has this week made me muse on the implications of the gap between science and public policy, truth and lies, opinion and fact.

I’ve been watching the mini-series Chernobyl, a dramatisation of the 1986 nuclear catastrophe. It begins with Soviet scientist Valery Legasov musing, two years after the accident: “What is the cost of lies? It’s not that we’ll mistake them for the truth. The real danger is that if we hear enough lies, then we no longer recognise the truth at all.” Time and again, as the disaster unfolds we watch science lose to party machinations and Soviet political considerations with horrifying results.

Now I’m not saying that talking about molecules of freedom in a democracy is the same as ignoring science during a nuclear disaster in the former Soviet Union, that would not be precise.

But the damaging consequences of politicians failing to heed science? That feels terrifyingly accurate.

Ebony Bennett is deputy director of The Australia Institute @ebony_bennett

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Victoria’s Electoral Laws Need Truth in Advertising and Fair Rules for New Entrants

Victoria should adopt truth in political advertising and address the unfairness created by its donation cap and public funding model.

Women still underrepresented in Australian parliaments

Ahead of International Women’s Day on 8 March, the Australia Institute has crunched the data on women’s representation in Australian parliaments.

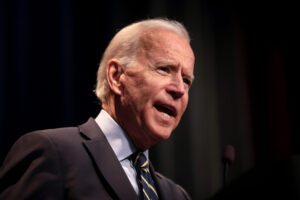

Biden’s Burden: Four Percentage Points, a Struggling Economy and a Fragile Democracy

In the United States, one of the men vying for the presidency faces 91 criminal charges in four concurrent criminal cases.