The RET, debt and the Direct Action bet

- The battle for jobs in the Hunter

- The Direct Action bet

- Weak excuses for a ‘real’ 20% RET

- The student debt crisis is real

- TAI in the media

- Infographic

The battle for jobs in the Hunter

A few weeks ago we told you that the chief spin doctor for the NSW Minerals Council Stephen Galilee had challenged Richard to a series of debates in the coal mining towns of the Hunter region. Richard accepted on the spot.

This week we announced that Richard will hit the road in November to discuss the future of jobs and the coal economy in the Hunter Valley. We’ve extended the invitation to Stephen Galilee to come and debate the facts but we haven’t heard any word yet.

Can coal and gas, horse breeding, viticulture and tourism co-exist? Don’t miss your chance to join the discussion in Muswellbrook, Gloucester and Newcastle from 11-13 November.

Details for each event can be found here.

Share the events on facebook here.

The Direct Action bet

A carbon price is central to any well designed emission reduction strategy. Indeed, a carbon price is the most equitable and efficient way to fund the ‘complementary measures’ or ‘direct actions’ that a well designed strategy must also rest on.

The Australia Institute has long argued that Australia needs a carbon price. Indeed, we were critical of the government, the Palmer United Party, Nick Xenophon and independent senators who voted it down. It was a backward step.

But, despite our views, and the views of many others, we do not have a carbon price. We are in what economists call ‘the world of the second best’, and in such a world we have to ask, and answer, hard questions such as ‘is something better than nothing?’ Is it better for the government to take $2.5 billion from consolidated revenue and use it to buy emission reductions? Or is it better that they do nothing and reduce the deficit?

These are hard choices that, unfortunately, have as much to do with political strategy as they do with climate policy. In answering them, the Institute has focused on the latter.

As well as pushing for a carbon price for nearly 20 years, the Institute has in more recent times been critical of the Coalition’s Direct Action plans. Some of the initial ideas suggested by the Coalition were unworkable and we have continued to question the likely administrative expense and effectiveness of the scheme. It is entirely unclear whether the Coalition’s $2.5 billion Direct Action fund will actually achieve enough abatement to allow Australia to hit its timid 5 per cent emission reduction target. Time will tell.

But until then, it is important to understand what Direct Action really is and where it fits in the policy toolbox.

The centrepiece of the climate policy negotiated by the ALP and the Greens under Julia Gillard’s Prime Ministership was the carbon price, but wrapped around it were tens of billions of dollars worth of what the government called ‘complementary measures’ and what the current government calls ‘direct actions’.

It is true that the direct action funding is a ‘pay the polluter scheme’, but it is also true that the previous government’s ‘contracts for closure scheme’ to pay coal fired power stations to shut down was to operate on exactly the same principles. It is also true that the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and Australian Renewable Energy Agency provide taxpayers money to fund emissions reductions.

The science of climate change continues to tell us that we need to act, and need to act more ambitiously and quickly than any country is currently acting. Australia’s 5 per cent emission reduction target is not nearly enough, a modest carbon price with 94.5 per cent free permits for big pollutes is not nearly enough and, of course, a $2.5 billion direct action fund is not nearly enough.

A carbon price alone will not tackle climate change. If we are serious about tackling climate change we need a full suite of price, regulatory and direct government interventions, and we need them soon. We also cannot continue to increase our coal exports.

Scrapping the carbon tax was a backward step, but the science tells us that we cannot afford to wait another two or five years for a possible change of government to take any action at all. The $2.5 billion allocated to buy emission reductions under the Direct Action scheme may not be nearly enough to meet Australia’s international obligations. With that in mind it is perhaps surprising that environmentalists are not arguing for more direct action rather than arguing for none.

Weak excuses for a ‘real’ 20% RET

The government has revealed its position on the Renewable Energy Target (RET), supporting the idea of a ‘real’ 20 per cent target. This position effectively cuts 60 per cent of the future growth in renewables.

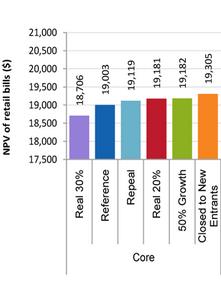

In order to reach this position the government handpicked a group of climate sceptics, fossil fuel interests and those opposed to government intervention to review the RET. The modelling that the RET review commissioned showed the cost of electricity to consumers under various possible changes to the RET.

The graph below, showing the cost to households, is cut straight from the report. The ‘Reference’ case (dark blue) is no change to the RET. The graph shows that moving to a ‘real’ 20 per cent target will increase electricity prices for households.

It is particularly surprising that the government has chosen the ‘real’ 20 per cent since the terms of reference for the review focused so heavily on cost of living impacts. Cost of living was so important that even the Prime Minister talked about the significant price pressures the RET was creating. It appears that the concern for household electricity prices has vanished with the government supporting a policy that will increase costs.

The government has put up two reasons for wanting the change. The first is that they have always advocated a ‘real’ 20 per cent target and the second is that circumstances have changed so the policy needs to be recalibrated. Taking a look at these two excuses reveals just how weak they really are.

A joint statement before the last federal election from Greg Hunt and Ian Macfarlane said “The Coalition is not proposing and has not proposed any changes to the target”. Before the election not once did Greg Hunt, Ian Macfarlane or Tony Abbott suggest that they wanted to reduce the target to a ‘real’ 20 per cent.

It is strange then that they claim they have always advocated a ‘real’ 20 per cent target.

In order to put forward the case for a recalibration of the target the government first needs to show that such a recalibration is required. They claim that it needs recalibrating because electricity demand has fallen. If falling electricity demand meant the policy was now substantially increasing electricity prices or causing the policy to fail, then perhaps it might need changes. However the RET is not causing any of these things.

In fact the RET is producing renewable energy while putting downward pressure on electricity prices. It is succeeding in creating a transition away from fossil fuel electricity generation. It seems strange to want to recalibrate a policy because it is being successful.

Perhaps the government is concerned that the big loser from the RET is coal fired electricity generators. If this is the case then the government should make that case. They should tell Australians that they should pay higher electricity prices to help protect coal fired power plants.

But for some reason they don’t want to tell Australians that!

The student debt crisis is real

When economic modelling and deregulation are both making the news on the same day, some see it as a good time to stop watching the news. But if you did, you’d miss a story of tremendous significance. What’s more, this time, the debt crisis is real.

Recently, modelling of the government’s planned university course fee deregulation showed that repayment costs for some students may be as much as triple and student debt levels more than double should the reforms be implemented. Education Minister Christopher Pyne has dismissed the research from the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling (NATSEM) as having “no credibility”, because the offices are based on the outskirts of the University of Canberra campus.

If this seems like a long bow to draw, you can try and track the logic. This is Pyne’s explanation for why the NATSEM work indicates the reform package is a bad one:

1. The university’s Vice-Chancellor Stephen Harper has been a vocal critic of the government’s deregulation agenda.

2. The modelling that suggests deregulation will price out many students and leave others with unmanageable debt was produced by an organisation who pays the university rent.

3. Therefore, NATSEM is beholden to its lessor.

If that’s not convincing, there is another alternative. Perhaps the modelling suggests that Pyne’s reforms will cause the cost of education to skyrocket because that’s exactly what they’ll do.

In the United States’ for-profit system, student fees have risen three times faster than inflation. For-profit universities, forced to compete amongst each other for the funds they need to continue educating, spend on average a quarter of their total running budgets on marketing alone. Forbes Magazine says America’s $1.2 trillion in student debt is “crippling students, parents and the economy”.

The Education Minister has made no secret that his reform proposal is based closely on the American tertiary system, even boasting about it in London just weeks before the details were announced. But while Mr Pyne is keen to sing its praises, he is less vocal on its problems.

NATSEM’s modelling indicates that moulding Australia’s education system into a lighter shade of the US would produce outcomes like those seen in the United States. Apparently, this conclusion is controversial.

Australia’s student population could be slogged with debt exceeding anything we’ve seen before. Nobody can be sure of what that will look like in 10 years time. But if the US experience can serve as a template – a function Mr Pyne seems happy to accept – so too should it serve as a warning.

It’s not all bad news, mind you. It is pleasing to see that the Government has set a precedent to reject the findings of economic modelling based on the interest of who it is that supported it.

With that in mind, The Australia Institute looks forward to the economic modelling of some of the country’s biggest mining companies enjoying this new standard of scrutiny.

TAI in the media

Watch Richard Denniss on The Drum

Greens under Christine Milne put protest ahead of progress

Fuel tax indexation: the pressure is on

Whitlamonics: The economics of social policies

LNG exports: Confusing foreign profits with Australian benefits

Infographic

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

HECS/HELP debt for low income earners is set to increase due to indexation

The indexation of HECS/HELP debt this year will leave people earning less than $62,000 with a bigger debt even after their repayments.

Tasmania’s fear of government debt is hurting the state

Tasmanians have been badly served by its government’s exaggerated fears about the condition of the state budget.

Redlight for Greenwashing: ASIC’s action on greenwashing | Jennifer Balding

“The growing interest in ESG is driving the biggest change to financial markets and financial reporting and disclosure standards we’ve actually seen in a generation. We’ve got to make sure that we are ready to meet the challenge of that change at every step of its development.”